Baby Ecology book is here! Learn more

Baby Ecology book is here!

- Home

- Baby-led feeding

What is baby-led feeding?

by Anya Dunham, PhD

You can practice baby-led feeding AND feed your baby purees by spoon. Key is that feeding (or, more accurately, eating) is baby-led.

Are you getting ready to introduce solid foods to your baby? Chances are, you’ve heard about the Baby-Led Weaning approach (or BLW for short). You might have also heard of baby-led feeding. Do these terms mean the same thing?

The Baby-Led Weaning (BLW) approach

The Baby-Led Weaning approach means letting babies feed themselves from the very start of weaning. (Note: BLW originated in the UK where ‘weaning’ means ‘adding complementary foods’, not ‘giving up breast-/formula-feeding’.)

In other words, instead of being spoon-fed by adults, babies feed themselves hand-held food. Some BLW advocates vouch for a very strict approach: do not introduce purees or spoon-feed your baby at all. “No more mush!”, they say.

This works for some babies and families, but not for all.

Healthy, full-term babies develop motor skills and mealtime communication abilities at different times. For example, on average, babies begin eating finger foods with ease at 8.5 months, but the range of normal for this milestone to emerge is quite wide: between 6 and 12 months.1,2 Some babies may need extra time mastering feeding: for example, babies with tongue-ties. The advice on when to introduce solid foods generally falls somewhere between 4 and 6 months (the World Health Organization recommends 6 months; read about 4 signs of readiness here). Many, but not all, 6-month-olds who are joining their family at the dinner table can do so in a “classic” BLW style.3

Strict ("no spoon-feeding, no purees") BLW works for many, but not all, 6-month-old babies.

But here is the good news: the main benefit of BLW has nothing to do with the shape or texture of food. The main benefit is that a baby chooses and controls how much and how fast she eats.4

And that – baby choosing how much of the food to eat, how fast, and whether to eat it at all – is key to baby-led feeding.

What is baby-led feeding?

Baby-led feeding does not limit the ways to present foods to a baby, as long as each food is of safe size, shape, texture, and temperature. Key to baby-led feeding is that eating is baby-led.

Our babies are born fully capable to like new foods and to eat according to their appetite and their needs.

All on their own

(an excerpt from my book, Baby Ecology)

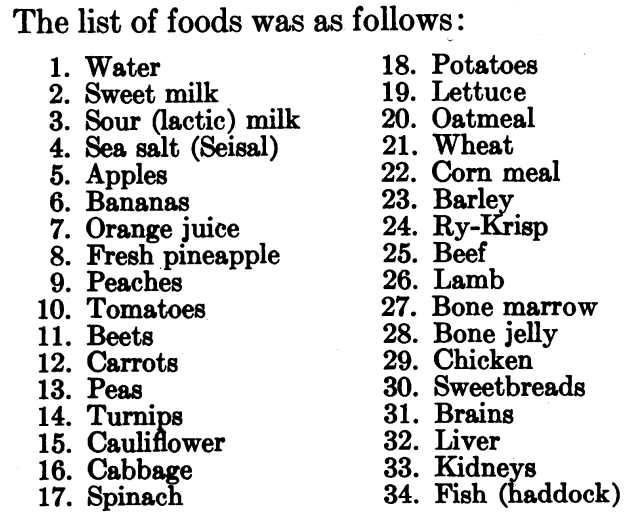

In the 1920s and 1930s, pediatrician Clara Davis and her team carried out unusual research5,6 that transformed the thinking on children’s eating. Her team followed 15 babies from when they were 4 months old all the way to 6 years old. Every day at every meal the children were offered the same selection of 34 foods, each served in a separate little dish, and allowed to eat whatever and how much they wanted, with no adult influence. The foods came from both plant and animal sources, provided all the necessary nutrients, were available fresh year-round, and required only very simple preparation.

From: Davis CM (1939) Results of self-selection of diets by young children. Canadian Medical Association Journal 41(3): 257-261

From: Davis CM (1939) Results of self-selection of diets by young children. Canadian Medical Association Journal 41(3): 257-261The results? Every child’s diet was different from every other child’s diet, but none showed the cereal and milk dominance with small amounts of fruit, eggs, and meat that was commonly thought to be proper for babies and children at the time. Meals often included strange-from-the-adult-perspective combinations (a breakfast of orange juice and liver, anyone?). All foods (except lettuce!) were tried by all children, especially in the early weeks, but distinct tastes formed over time. As children grew, they changed how much protein they consumed, consistent with the change in energy requirements that comes with growth and increased activity. Children who took no or very little cow’s milk for considerable periods of time still developed strong bones. All children grew healthy and strong, even those who had rickets at the beginning of the study.

The Davis study had limitations: only 15 children were included, and, perhaps due to the challenges of the 1930s, the results were not presented in detail. Replicating a study like this today would not be possible for ethical reasons, and that’s a good thing. (This experiment was run in a specially set up orphanage.) Yet, even with these limitations in mind, this pioneering research does strongly suggest that babies are born capable eaters.

And here is something more recent studies tell us: to retain these innate capabilities to eat well and to eat to appetite, babies do need our support. They need us to lead in these 2 major ways:

- They need us to offer them a variety of nutrient-dense foods. Scientists believe that the “trick” in the Davis study was the food list. If overly sweet or salty fried foods had been included in their day-to-day diet, children would have likely developed a preference for these energy-dense but nutrient-poor choices,7 and their growth and health would have likely been affected. I imagine the same would be true if processed, empty-calorie snacks were a regular part of the children's diet. Our babies need us to continue offering them foods they seem to initially dislike (here is why).

- They need us to offer them food without any pressure or restrictions. Control or pressure during feeding reduces a baby’s ability to self-regulate.7 In one study, when mothers were responsive in their feeding, babies self-corrected their growth trajectories: those who gained weight slowly in the early months began growing faster between 6 and 12 months. But when mothers were controlling — for example, forcing, repositioning, or distracting their babies in an effort to make them eat more — the opposite pattern was observed: smaller babies grew even slower! This shows that controlling is, in fact, counterproductive.8 Controlling overrides babies’ internal hunger and fulness clues.9

(Babies also eat best when they are comfortable. See our high chair set up and why it's never a good idea to feed baby in a car seat.)

Baby-led feeding can be done in many ways: by breast, bottle, BLW, or spoon

I found Ellyn Satter’s approach10, the Division of Responsibility (DOR, or sDOR), most helpful in shaping my thinking around babies' and children’s eating. If you want to learn about it, I highly recommend Ellyn’s book, Child of Mine: Feeding with Love and Good Sense. In a nutshell:

- Parents set up a nurturing feeding environment and provide nutritious foods at regular times

- Babies decide how much of each food to eat and whether to eat it at all

So what is baby-led feeding? It's a feeding style where we create a supportive feeding environment and then trust our babies to eat as much as they need; we predictably offer nutritious food and let our babies’ lead.

You can follow baby-led feeding every time you feed your baby, from day 1.

In my book, Baby Ecology, I do a deeper dive into the science that supports baby-led feeding and show, using real-life examples, how you can do it throughout your baby's first year.

- You can follow baby-led feeding while breast- or bottle-feeding.

- You can follow it with BLW; BLW is one type of baby-led feeding.

- You can also spoon-feed pureed foods and still follow baby-led feeding.

I chose spoon-feeding for my babies when they first started solids. For us, it was a short phase that lasted a few weeks and gradually led to competent self-feeding. Many families combine feeding styles right from the start. They offer their babies both purees from a spoon and pieces of food to self-feed. Either way, nutritious foods and responsive feeding are key.

I wish you a smooth start to this new stage that will last a lifetime: your son or daughter joining you at the family table.

References

References

1. Carruth BR, Skinner JD (2002) Feeding behaviors and other motor development in healthy children (2—24 Months). Journal of the American College of Nutrition 21(2): 88-96

2. Skinner JD et al (1998) Mealtime communication patterns of infants from 2 to 24 months of age. Journal of Nutrition Education 30(1): 8-16

3. Cameron SL, Taylor RW, Heath A-LM (2013) Parent-led or baby-led? Associations between complementary feeding practices and health-related behaviours in a survey of New Zealand families. BMJ Open 3(12): e003946

4. Rapley G et al (2015) Baby-Led Weaning: a new frontier? ICAN: Infant, Child, and Adolescent Nutrition 7(2): 77-85

5. Davis CM (1928) Self-selection of diet by newly weaned infants: an experimental study. American Journal of Diseases of Children 36(4): 651-679

6. Davis CM (1939) Results of self-selection of diets by young children. Canadian Medical Association Journal 41(3): 257-261

7. Schwartz C et al (2011) Development of healthy eating habits early in life. Review of recent evidence and selected guidelines. Appetite 57(3): 796-807

8. Farrow C, Blissett J (2006) Does maternal control during feeding moderate early infant weight gain? Pediatrics 118(2): e293-e298

9. Black MM, Aboud FE (2011) Responsive feeding is embedded in a theoretical framework of responsive parenting. The Journal of Nutrition 141(3): 490-494

10. Satter E (2000) Child of Mine: feeding with love and good sense (3rd edition). Bull Publishing Company, Boulder, CO, USA

Using hundreds of scientific studies, Baby Ecology connects the dots to help you create the best environment for sleep, feeding, care, and play for your baby.

Warmly,

Anya